-

PABLO PICASSO

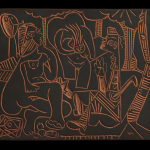

Le déjeuner sur l'herbe (A. R. 517), 1964Terracotta rectangular plaque, painted in black and engraved51 x 61.5 cm

20 1/8 x 24 1/8 in.Proof aside from a numbered edition of 50‘Manet’s concern was to relate a painting to a painting: Picasso’s was to relate a painter to a painter. What was at stake was not only his own power as...‘Manet’s concern was to relate a painting to a painting: Picasso’s was to relate a painter to a painter. What was at stake was not only his own power as a painter but his power as a demiurge: the power to metamorphose certain objects in the world of reality which are also, and equally, paintings in a museum. Manet had freed him from the past and given him a new creative impulse’ (Bernadac, op. cit., p. 72).

Conceived and executed in 1964, Pablo Picasso’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (A.R. 517) enacts a seminal artistic dialogue between two major figures in modern art history.

Upon his first encounter with Édouard Manet’s 1863 Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe in 1932 (Musee d’Orsay, Paris), Picasso famously stated: ‘I tell myself, tribulations for later.’ (quoted in Léal, Piot and Bernadac, op. cit., p. 430). Over three decades, he produced around forty variations of Manet’s composition, culminating in a diverse oeuvre that includes twenty-seven paintings, drawings, prints, and ceramics. This extensive body of work reflects Picasso’s desire to bring to modernity the long- lasting art historical discourse culminating in Manet’s masterpiece, deeply rooted in the works of masters such as Titian, Rembrandt, Velázquez, and Delacroix.

In the present work, Picasso reconceptualises Manet’s scene, depicting three of the four original figures while playing with their reciprocal placement, scale, and compositional narratives. Immersed in a pastoral setting composed of trees and other natural elements, the characters take centre stage, accompanying their conversation with an accentuated gestural expressiveness. Each of the figures operates as an independent entity, absorbed in their actions, creating an atmosphere of quiet intimacy. The act of dining outdoors evokes the simple, pastoral life Picasso experienced when he lived in the southern French countryside. In this work, food is indeed a central motif, emphasising its agency as a vital necessity for the body and as a vehicle for social interaction. Through solid outlines and clear shapes, Picasso re-appropriates the essence of the original composition. This approach aligns with his broader stylistic evolution, particularly in the 1960s, when he adopted a more abstract aesthetic language. If the female forms exhibit graceful curves, highlighting their femininity and sensuality, the male figure is rendered with angular and straight lines. Adding a further interpretative layer, this deliberate graphic expedient serves to underscore contemporary societal roles and perceptions of gender. The inclusion of the fully clothed male figure alongside nude women resonates with Manet’s original scandalous juxtaposition, retaining the provocative spirit of this confrontation while situating it within a modern context. Picasso had long shown a great interest in the theme of the nude, yet this terracotta appears to relate in part to the theme of the artist and his model which would come to figure so often in his work.

Picasso’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe stands as a profound example of the artist’s ability to engage critically with historical works, by masterfully bending the medium to his creative flair. As an artist’s proof, this rectangular terracotta plaque is distinct from the limited edition of fifty and its designation as Exemplaire Éditeur highlights its unique position, as publisher’s proofs were often retained within the artist’s studio as a personal reference.

Provenance

Private Collection, United States.

Literature

M.-L. Bernadac in Late Picasso: Paintings, Sculpture, Drawings, Prints 1953-1972, exh. cat., Musée national dʼart moderne,

Tate Gallery, Paris and London, 1988.

G. Bloch. Pablo Picasso. vol. 3, Catalogue of the Printed Ceramics, 1949-1971, Editions Kornfeld et Klipstein. Bern, 1972,

p. 141, no. 163, illustrated.

G. Ramié. Picassoʼs Ceramics, Secker & Warburg, London, 1975, p. 290, no. 640, illustrated, and p. 257.

A. Ramié. Picasso, Catalogue de lʼouvre gravé céramique 1949-1971, Paris 1988, no. 517.

B. Léal, C. Piot and M.-L.Bernadac, The Ultimate Picasso, New York, 2003.

K. Roth in Picasso in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, G. Tinterow and S. Alyson Stein, eds., exh. cat.,

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2010, p. 317, no. C1, illustrated.