-

Antonio Fabrés

Barcelona, 1854 – Rome, 1938

Silia and her Daughter Cressida imprisoned

Oil on canvas

104 x 166 cm

Inscription at the lower right: “dedicada a Tina de Strobel”

Inscribed at the lower right: “A. Fabrés – México 2 – 1904”

Awards1875 - Award-scholarship in Rome1885 - Award in London1887 - Award in Madrid1888 - Award in Vienna1901 - Award in París1902 - Award in Lió1908 - Inspector general de Belles Arts in Mexico.MuseumsRomeEstocolmoBuenos AiresPhiladelphiaNantesBerlinMadridLa CoruñaMuseu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, MNAC, BarcelonaAntonio Fabrés y Costa, who studied at the School of Fine Arts in Barcelona, is one of the most important Spanish artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1875, he was awarded a grant to travel to Rome, where he studied the work of Mariano Fortuny, who had died at his artistic peak the previous year. In Rome, Fabrés specialised in historical and orientalist figures, depicted with notable realism in the preciosista style. In 1892, having achieved international fame, he moved to Paris, in part thanks to the support of the influential art dealer Adolphe Goupilhe. During the World Fair of 1900, he met the sculptor Jesús Contrera, whom the Governor of Mexico had entrusted with finding a professor in Europe for the painting class at the Academia de Bellas Artes de San Carlos in Mexico City. Between 1902 and 1907 Fabrés lived and taught there, participating in the evolution of local painting towards realism. The fame and reputation he acquired obtained him the project of supervising the decoration of the Sala de Armas of the Mexican president Porfirio Díaz.

The most important painting executed by Fabrés during his Mexico period, was Silia and her Daughter Cressida imprisoned, which conforms to the Neo-Pompeian genre of history painting, characterised by its archaeologically accurate reconstruction of interiors, luxurious objects and clothing. In comparison to Fabrés’ painting The Drunkards (Museo de San Carlos, Mexico City, fig. 1), an impressive work which the artist used to introduce himself to his Mexican clientele, the painting of Silia can be considered the ultimate demonstration of the intellectual powers and technical skills of the new director of the Academia. In this work Fabrés rose to the challenge of the most highly esteemed pictorial genre, history painting, temporarily setting aside his successful series of genre works. In addition, the painting tested his technical skills, offering numerous challenges: the representation of candlelight, the original foreshortening of the bodies, and in particular the evocation of the pathos of the human sentiments. The cry of fear which transforms Silia’s classical face when she believes her daughter dead, is theatrically emphasised by the light emanating from below, and truly memorable.

Fig 1. Antonio Fabrés y Costa, The Drunkard (1896).

Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico.

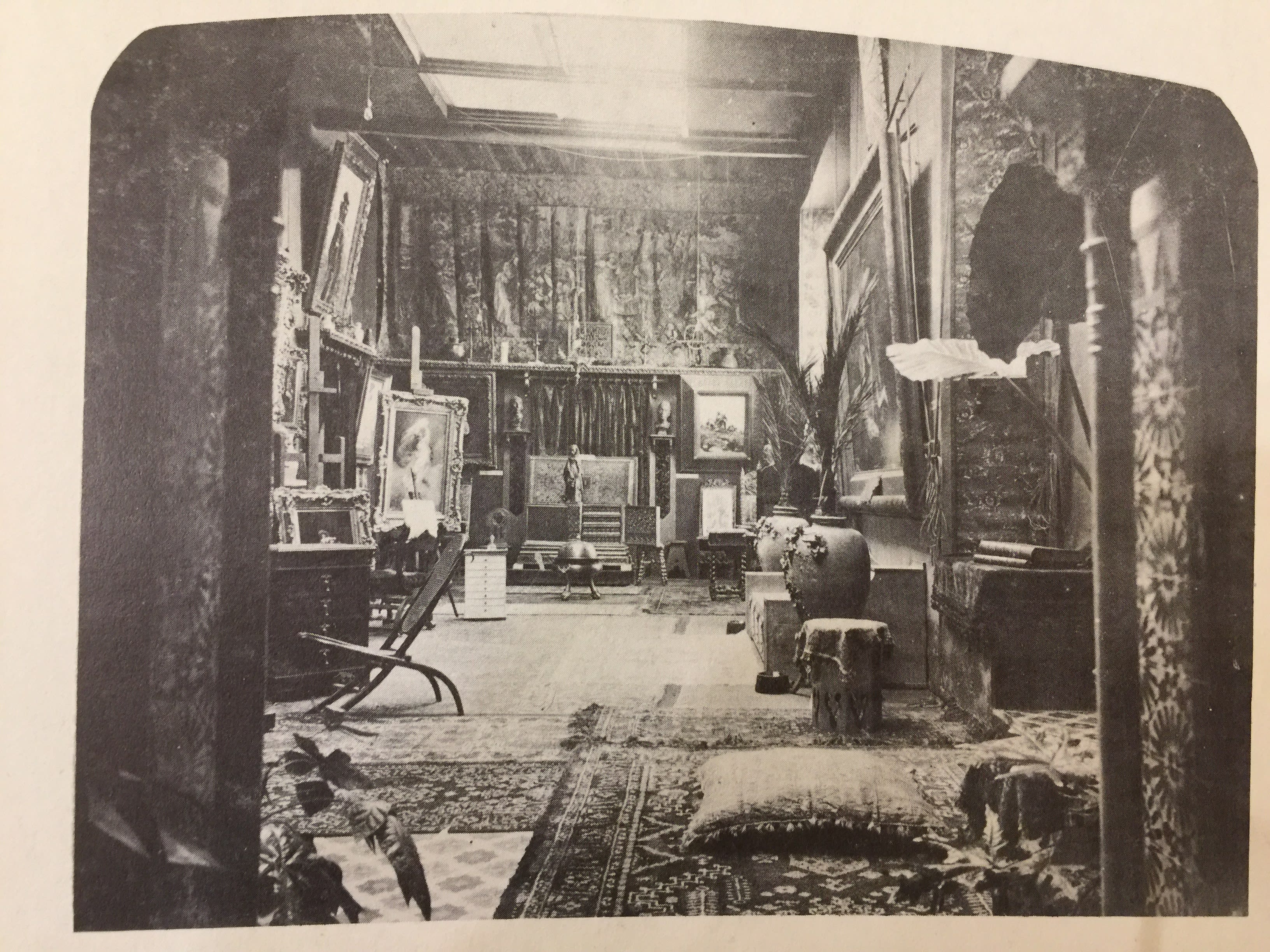

Finally appreciated after years of neglect, Silia and her Daughter Cressida imprisoned is documented in Fabrés’ studio in the Academia de San Carlos in a photograph of the period (Moreno 1981, p.39). In addition, it was the most important painting within the temporary donation to be made in 1925 to the Museo de Bellas Artes in Barcelona, although that donation was ultimately not made. The painting is visible in the centre of the photograph of the Sala de la Reina Regente, where it is framed by curtains to emphasise its theatrical character (Moreno 1981, p.70). The artist himself subsequently donated it to his student Tina De Strobel, who is mentioned in the dedication of the painting. A document of 1931 relating to the sale of the painting by De Strobel’s husband indicates that the subject is “Silia in the story of Nero”. This reference is incomplete, and is probably based on a summary by De Strobel. As recorded in the Annals of Tacitus (XVI, 20), Silia was the wife of a senator. Her story is one of the episodes that followed the Pisonian conspiracy. Among the numerous senators and patricians whom Nero obliged to commit suicide, Roman historians, particularly Suetonius and Tacitus, devoted considerable space to the writer Petronius, arbiter elegantiarum of the imperial court.

Due to Silia’s close relationship with the deceased writer, she was accused of having made Nero’s nocturnal vices public, given that she had been a witness to them. Silia was thus condemned to exile. The French novelist Frédéric Soulié devoted considerable space to Silia in one of his Romans historiques du Languedoc (Paris, Ambrois Dupont, 1836) based on this information, focusing on the early years of Christianity in France. The licentious wife of the austere patrician Sillanus, this captivating Silia was banished by Nero to exile in Nîmes, the southern centre of Gaul, where she lived in luxury, courted by both the powerful duumvir Bibulus, and Faustus, the tribune of the 10th Legion. Without Silia’s knowledge, two of her children, the adolescent Gneus and Cressida, arrived in France, stripped of their possessions and banished, following the forced suicide of their father. During a sumptuous banquet Silia and Faustus were accused of having conspired against the imperial power and she was imprisoned, wearing her purple gown, a wreath of flowers in her hair and her precious jewels. Her unconscious daughter Cressida was locked up in the same cell. Fabrés’ painting depicts the moment of the encounter between mother and daughter described by Soulié. Believing her daughter to be dead, Silia desperately clasps the young girl in her arms. In the darkness of the cell, only illuminated by a faint light entering from the classical-style skylight, the two female figures stand out: the young Cressida, wearing a white tunic of virginal purity, and the licentious Silla, dressed in a tunic of Spartan style, which the novel describes in precise detail and which is split at the sides to reveal her legs.

It is possible that Soulié’s novel may have attracted Fabrés’ attention precisely due to the subject of Nero, the last representative of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Although he does not appear in the novel, Nero is a key figure in the narrative. Soulié’s account of Silia, written in 1836, seems to run through the literary and visual works devoted Nero that were produced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, all inspired by the vivid descriptions offered by Suetonius and Tacitus. The guiding thread of these works is the Emperor’s corruption and cruelty, which was the subject of a lengthy article by Domenico Gnoli published in the influential journal Nuova Antologia, a text that offers proof of critics’ interest in this subject as well as artists and writers. Nero was also the subject of a historical verse drama by Pietro Cossa of 1873, followed by his Messalina three years later. One year after that, the sculptor Emilio Gallori depicted a decadent Nero dressed as a Woman (Florence, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna), while in 1876 in Rome the Polish artist Henryk Siemiradzki produced Nero’s Torches (Krakow, National Museum, fig. 2), a masterpiece of the genre, characterised by its theatrical and dramatic composition. Finally, in the same year Giovanni Muzzioli painted the more intimate scene known as The Vengeance of Poppaea (Modena, Museo civico d’arte), in which Octavia’s head is presented to the Emperor. In 1888 Muzzioli achieved enormous success with The Funeral of Britannicus (fig. 3), who was poisoned by his servant Locusta on Nero’s behest. In an ongoing dialogue between literature and the visual arts, Siemiradzki’s painting inspired one of the most dramatic scenes in Quo vadis, Henryk Sienkiewicz’s historical novel published in 1895. In 1904, Fabrés also focused on the subject of Nero, although leaving the Emperor as an off-stage character and choosing to use the melodramatic tone characteristic of the Neo-Pompeian painters since the 1880s. The figure of Silia, who throws herself in desperation on her unconscious and seemingly dead daughter, recalls that of Octavia who in Muzzioli’s painting weeps for the premature death of her brother, in a style that “goes beyond archaeological-scholarly information and engages with the mechanism of melodrama and the veristic novel” (Querci, in Alma-Tadema e la nostalgia dell’antico, p.232).

Teresa Sacchi Lodispoto

Fig 2. Henryk Siemiradzki, Nero’s torches (1882)

National Museum, Krakow.

Fig 3. Giovanni Muzzioli, The Funeral of Britannicus (1888)

Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna, Ferrara.

Fabrés workshop at Academia de San Carlos

(Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes).

Bibliography

- Alma-Tadema e la nostalgia dell’antico, exhib. cat., introduction by Eugenia Querci and Stefano De Caro, Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, 2007-08, Milan 2007.

- Domenico Gnoli, “Nerone nell’arte contemporanea”, in Nuova Antologia, XI, 9, pp. 55-75.

- Salvador Moreno, El pintor Antonio Fabrés, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Méjico, 1981.